|

|

|

Follow Mark on Facebook for more stories |

||

|

|||||

|

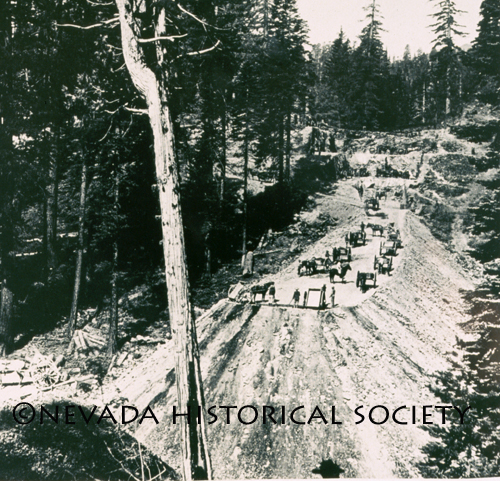

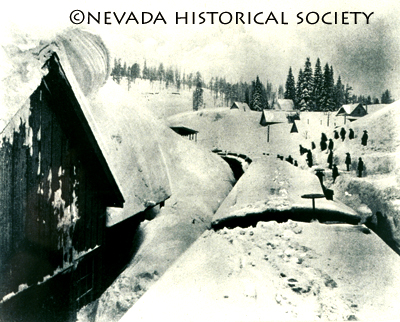

Tahoe Nugget #147 Nitroglycerine & Black Powder In order to conquer the Sierra crest, the most challenging section of America's first transcontinental railroad, Central Pacific Railroad hired thousands of Chinese men to shovel, pick and blast their way through the formidable granite spine. The Chinese immigrants were often called "Celestials" because they referred to their native land as the Celestial Kingdom. Incredibly, the railroad was built using only human and animal sweat and muscle – no machines. Deep gorges were filled with rock and soil brought in by small carts pulled by horse and mule teams. (See photo #5). Contracted from China specifically for this project, the men were paid $30 to $35 per month. During the winter of 1866-67, construction workers endured 44 storms that dumped nearly 45 feet of snow and generated deadly avalanches. Despite the formidable obstacles of ice and granite, rail by rail the hard-working Chinese crews pushed the track east, reaching Donner Summit on November 30, 1867. Engineering and constructing a railroad through the Sierra Nevada had long been considered an impossible folly. William Tecumseh Sherman, who later became a Union General in the Civil war, was an experienced engineer and surveyor familiar with the Sierra Nevada. He wrote his brother of the project; "If it is ever built, it will be the work of giants." It took Theodore Judah, a brilliant young engineer from New York, and an army of 12,000 diminutive Chinese workers to prove the skeptics wrong. The track through the mountains was built along steep-sided, avalanche-prone slopes. Sometimes the railroad clung to bare granite cliffs. Nine tunnels were chipped out, totaling 5,158 feet in length. At Donner Summit, Tunnel No. 6 was carved through 1,659 feet of solid granite. Despite non-stop digging and 300 kegs of black powder a day, the rock was so hard that the Chinese laborers could advance only 8 to 12 inches per day. To expedite the work, a vertical shaft seventy-five feet deep was sunk so that crews could work four headers, two from the middle out and two towards the shaft. (The cap to this shaft can still be seen today just off Highway 40 – see photo #3). Blasting powder had proved adequate until crews reached the obdurate Sierra granite, but after more than a year using it ineffectively on the long Summit Tunnel, C.P. deployed a new high explosive called nitroglycerin. First discovered in 1846, Alfred Nobel had patented an improved manufacturing process on October 24, 1865. Nitro is a clear, odorless, volatile oil thirteen times more powerful than gunpowder and is the active ingredient in dynamite. Nitroglycerin detonates almost instantly, producing a large volume of gas and a powerful shock wave that blasts rock apart. When C.P. began using nitro to bore the Summit Tunnel in January 1867, they were probably the first to do so in the United States. Nitro had a nasty reputation for exploding at unexpected times. In April 1866, the San Francisco Chronicle described a terrible tragedy that resulted when someone tried to open a leaking case of nitroglycerin that had just arrived by steamer from Hamburg, Germany: "The explosion occurred in the office of Wells Fargo & Company by which eight persons lost their lives. It also caused a quarter of a million dollars in damage to the commercial district." To avoid a similar experience, the railroad company manufactured the nitro on Donner Summit as needed, where it doubled the speed of tunnel excavation. Even so, the Summit Tunnel was not completed until May 3, 1867; nearly two years after the work began. Constructing a railroad 88 miles over the rugged Sierra Range between Newcastle and Truckee, California, had taken 12,000 men 38 months (February 1865 to April 1868). In comparison, the railroad from Truckee across the desert to Promontory, Utah, a distance of 571 miles, took only 5,000 men just one year and 27 days. General Sherman was right — conquering the Sierra did take the work of giants. Tahoe Nuggets are now archived at www.thestormking.com Photo #1: 1881 advertisement in Reno Gazette Journal

|

|||||

|