|

|

|

Follow Mark on Facebook for more stories |

||

|

|||||

|

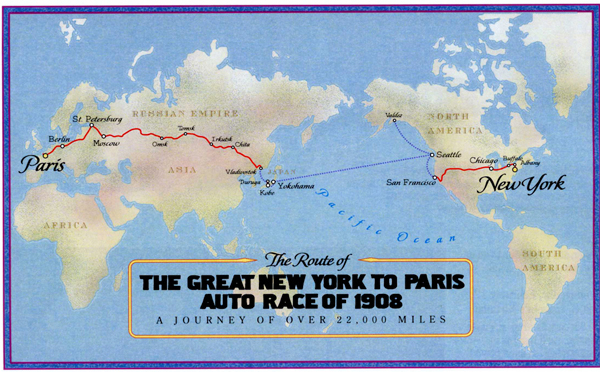

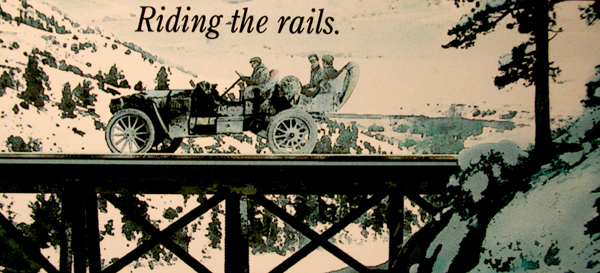

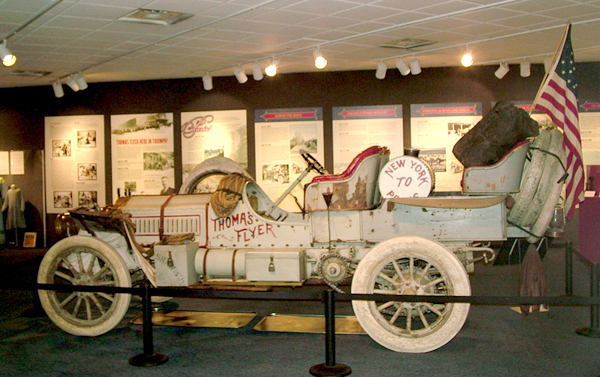

Tahoe Nugget #137 Great Auto Race 1908 Drivers, start your engines! On May 30, 2008, dozens of enthusiasts will be participating in a commemorative re-creation of "The Greatest Auto Race" of 1908, held 100 years ago. Then, as now, the goal is to drive from New York City to Paris, France, in the fastest time. Today we take sleek high-performance automobiles for granted, but early in the 20th century most people in rural America were skeptical that the new "gasoline buggies" would ever replace a good horse. In order to prove them wrong, automakers and the media organized an epic endurance contest to prove the mettle of the new horseless carriage. In 1907, the Paris newspaper Le Matin began promoting the idea for a long, challenging auto race. The New York Times teamed up with Le Matin to co-sponsor "the toughest race ever devised." The editors charted a global course so grueling, so brutal, it seemed that no automobile (or man) could withstand the punishment. The New York to Paris race seemed to meet that criterion. It was an unprecedented automotive odyssey of more than 22,000 miles that would take nearly six months and span three continents. The race started in February so that entrants would be forced to drive across the United States during winter, a feat never previously accomplished by automobile. The next leg of the race went on to Alaska, for an attempt to drive over the frozen Bering Straight, towards Siberia, Russia and eventually Paris. It was a crazy idea and hardly anyone really believed it could be done, but 17 men representing four countries dared to try. It was crisp and cold in New York City on February 12, 1908, where 250,000 people had gathered in Times Square to cheer the start of the Great Race. Lined up were six automobiles, representing the best auto technology yet produced by the world's superpowers of the day — France, Italy, Germany and the United States. France had entered three cars, while the other countries each ran one. All the cars had been modified for the race (Germany's vehicle was designed and built with huge gas tanks and other innovative adaptations), with the exception of the American-made car, which was a last minute entry. Just days before the race, the E.R. Thomas Motor Company decided to enter its Thomas Flyer, a 60-horsepower stock production four-cylinder, four-speed they picked up off their factory lot in Buffalo, N.Y. One of the few adjustments made to the Flyer was to lash two long wooden planks to the side fenders to serve as tracks in mud and snow, or as an emergency bridge. Mechanics also cut holes in the floorboard so heat from the engine could warm the driver's feet. Shortly after the racers bolted out of New York City they all ran into trouble with snowstorms in upstate New York and across the Midwest, where hazardous weather conditions and a lack of roads forced the Americans to use railroad tracks at times. One of the French cars traveled only 44 miles before it bogged down and dropped out of the race, and France lost another vehicle in Iowa due to mechanical breakdown. The Flyer was the first to reach Chicago, Illinois, on Feb. 25, but the other three competitors all arrived within the next four days. The Thomas Flyer crew maintained their lead as they raced across America, where enthusiastic crowds gathered to cheer the team on and to write their name or initials on the car. The crew spent all day driving as fast as they could and long nights working on repairs. One newspaper described them as, "fierce-looking, wild-eyed men who travel without sleep and without food." A New York Times reporter rode along with the Flyer's crew, and his dispatches kept the American racers' progress on the front page of the Times for the duration of the event. In Wyoming, the best wintertime route turned out to be the Union Pacific tracks, while in Utah the Americans followed an old emigrant wagon trail and battled blinding sandstorms until they were forced onto the bumpy railroad ties of Southern Pacific. Fifty miles east of Tonopah, Nevada, the Flyer's transmission cracked under the strain, which forced the team mechanic, George Schuster, to hire a horse for $20 from a nearby rancher to reach Tonopah for help. Fortunately, a local doctor allowed Schuster to dismantle the physician's own Thomas Flyer for the needed parts and the American team headed south to cross Death Valley into California. They reached San Francisco on March 24 to great fanfare. It had taken them 41 days, 8 hours and 15 minutes to drive nearly 4,000 miles from Times Square, but they had no time to celebrate. The crew immediately set about preparing their vehicle for the perils of crossing Alaska and Siberia. On March 27, the Flyer was loaded onto a ship for its journey to Valdez, Alaska, which it reached on April 8. Meanwhile, the Italians were still 12 days from San Francisco, with the French 250 miles behind them. When the trailing Germans ran into serious mechanical difficulties, they loaded their disabled vehicle onto a train bound for Seattle to catch a ship sailing for Valdez. It was a bad decision that would come back to haunt them in France where the judges would penalize them 15 days for failing to drive across the western U.S. The Thomas Flyer was greeted in Valdez by cheering crowds and a marching band, but the snow was so deep in town that the car couldn't even be driven off the dock. It was obviously impossible to drive through the Alaska Territory toward the Bering Straight so the race organizers sent a telegram ordering the American's back to Seattle. The Flyer was the only racecar to reach Alaska. On April 14, the French and Italian teams sailed from Seattle for Japan. The train carrying the German car reached the Pacific Northwest a few days later, where it was placed on an Asia-bound freighter on April 19. The detoured Americans finally returned to Seattle on April 21 where the Flyer was loaded aboard a steamship bound for Kobe, Japan. During the 18-day sea voyage, the Flyer crew learned that the race committee had awarded them a 15- day credit for having gone to Alaska. After crossing Japan during the middle of May, the Flyer reached Vladivostok, Siberia, where it had rained for 17 out of the previous 20 days. The road was a quagmire of mud, so after 100 miles of constantly bogging down, the Americans abandoned the road for the Trans-Siberian Railroad tracks. At this point, the Flyer was ahead of the Italians, but behind the German team, who had repaired their vehicle and skipped Japan. The French had pulled their last car from the contest and the Great Race was now down to three automobiles. For two months, the German team battled the Americans for the lead. Drivers and mechanics were exhausted and every mile took a Herculean effort. At one point, the crew of the Flyer stopped to pull the Germans out of the mud, after which it took 40 soldiers to do the same for the Thomas Flyer. Their vehicles were so beat up that they wobbled down the road. Mechanical trouble plagued both automobiles. By now the Italians were so far behind that they were effectively out of the race. The German car rolled into Paris on July 26, four days before the Americans. In an all-out burst of fanatical driving, Schuster roared into Paris on July 30, but not before being stopped and ticketed by a French policeman for a broken headlight violation. Germany's victory celebration was short-lived, however, as the 15-day penalty for taking the train in the U.S., plus the 15-day credit given to the Thomas Flyer for reaching Alaska, catapulted the Americans into first place. The Great Race took 169 days of fierce competition and incredible endurance to win, and it convinced many skeptics that automobiles were indeed as good as a horse. Photographs 1 through 4 courtesy National Automobile Museum Photo #1: Map of the Great Race route.

|

|||||

|